Who does what and how to support them

Engineering Management in a sentence

It sounds so simple. Match the ‘resources’ to the ‘missions’. Every spreadsheet pusher should be able to do it.

That’s how teams fail and engineer careers are ruined.

Their is an art in mastering the balance between what your company needs, what your engineers need, and what your team needs.

Who does what

There are 3 layers in how I’ve seen managers approach this challenge.

Layer #1 - Efficiency (what your company needs)

What needs to be done RIGHT NOW.

For every need, you take the most capable person in that area. The same people keep doing the same kind of projects again and again, as it’s the most efficient use of their time.

Layer #2 - Advancement & challenge (what your engineers need)

Trying to take into account your engineers’ career aspirations.

So if a mid level engineer wants to become a manager someday, they’ll get more opportunities to lead others, mentor new hires, etc. The same holds for trying to keep the engineers challenged, providing them growth opportunities (often at the price of efficiency).

You also need to take into account if there is a promotion on the line. Especially at more senior levels, engineers will need to get the right opportunities to demonstrate their readiness.

Some well intending managers lean into this one too much - letting engineers work on sexy side projects that have nothing to do with the company’s needs (but are done in a ‘super modern stack’ that keeps the engineers happy).

Most of your probably experienced it - the play between efficiency and people growth is super tricky. You cannot lean too hard to either direction, and you constantly need to reassess and update your decisions.

Layer #3 - Durability/Flexibility (what your team needs)

Sometimes, neither efficiency or people advancement is the right decision.

For example, let’s take a shitty legacy system your team maintains. You have one engineer who is familiar with it, and handles most of the noise there. They don’t care that much about it, and don’t mind doing it alone.

Everybody else hates it, and don’t want to touch it even with a stick. What do you do?

Maybe you can afford to depend on a single engineer. But maybe not - what happens if she takes a vacation, or moves to another team?

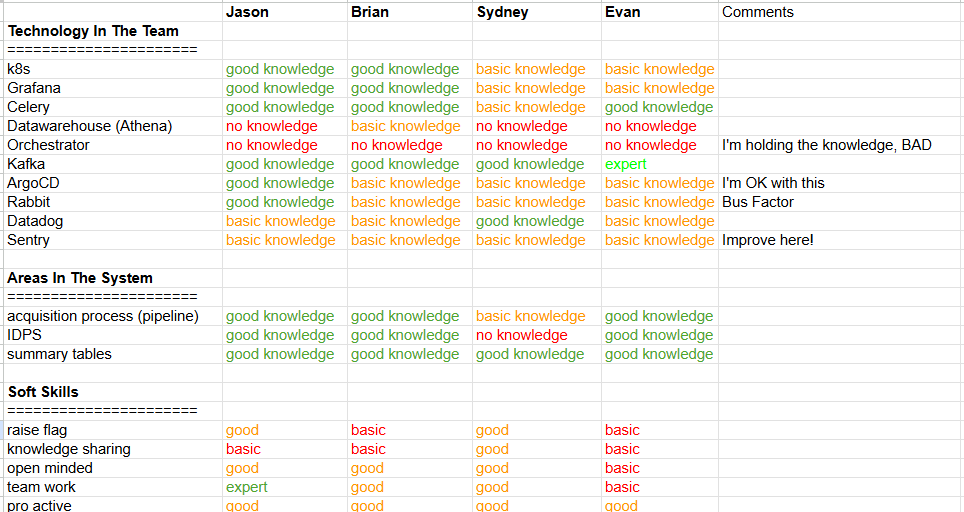

One of the exercises I do with EMs is to create a ‘knowledge map’ of your team. You can use any categories you’d like - tech stack, system you support, soft skills, etc.

Here’s an example:

Then, you can read it in 2 ways:

By rows - trying to understand if the current situation is acceptable. No rules or best practices here, just a lot of good judgement skills.

By columns - helping you with layer #2, your engineers’ growth. It’s a simple way to see what opportunities you can offer them.

Common traps

There are 2 common ones, which are closely connected:

Inertia - you find a pattern that works for you, and just keep repeating it. It may be by labeling an engineer as ‘needs to be challenged’, consistently giving them the sexier projects. Or, it can be a process - a certain way to share knowledge and rotate ownership.

Once you fall into a comfortable routine, it’s very hard to fight the inertia. If, for example, your company enters a crisis mode and needs something different from your team, there can be a lot of resistance.Activation energy - one of the reasons inertia is so hard to battle is that there is a high price to pay for a change. Throwing an engineer into a new domain is always slower, harder, and can be more frustrating. Sometimes you need to find those small steps that make it easier to continue.

…And how to support them

So you’ve mastered the tricky balance between what the company needs, what your engineers need, and what your team needs.

The 2nd part is not easier - how do you support the engineers in the missions assigned to them?

A common formula is: “the more senior they are, the less support they need”. So you spend the time mentoring the juniors, and let the senior+ engineers roam free.

If you are all-in on efficiency, meaning people work at similar tasks, this might work. But if you start moving people around to support layers #2 and #3, you’ll hurt your team with that approach.

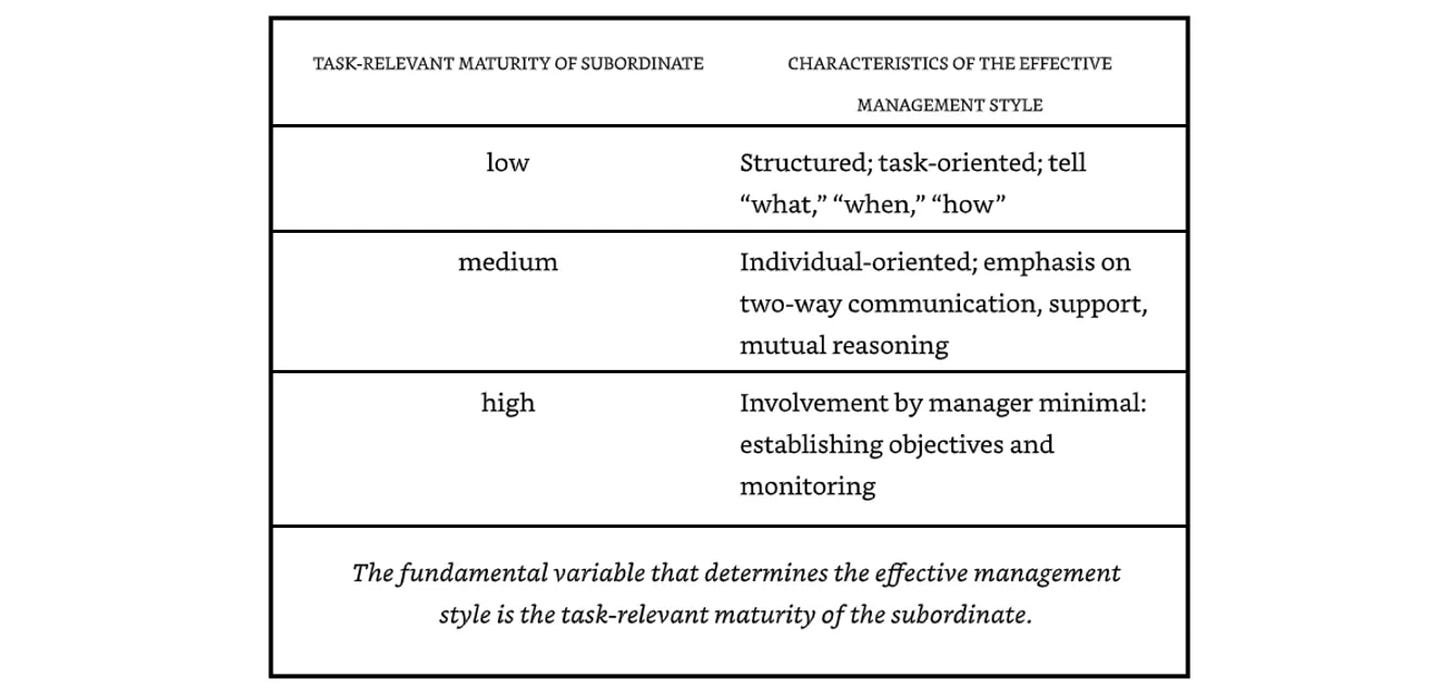

In High Output Management, Andy Grove coined the term “Task-relevant maturity”. Basically it means that we choose our approach not based on the seniority of the person, but based on their seniority in the specific task:

The practices (and language) in the table from the book are a bit outdated, but the concept still holds - especially if the nature of the task changes.

Final words

“Who does what” is an underrated decision. You might spend only 10 minutes on something that can have impact on an engineer’s career 5 years later.

With great power… :)

On a more personal note: Two years ago, I started exchanging comments with a fellow newsletter writer. We became good friends, meeting in person and collaborating on a few projects together.

I find his writing on mental models and thinking processes genuinely useful, and I’ve referenced it consistently across my articles. After 100+ posts, Michał Poczwardowski is running a condensed workshop: Get Unstuck: 5 Decision-Making Laws for Engineering & Product Leaders.

I honestly believe it’ll be valuable for any engineering manager. I bought a ticket and will be there myself :)

(Not sponsored - just a genuine recommendation.)

Discover weekly

Newsletters I read in 2025 by Gilad Naor (almost exactly as my list)

Just forcing ourselves to write things down or put them on a scale triggers reflection.

That's why I find "knowledge maps" to be something worth implementing, and I use them in a similar format.

P.S. Thanks for all the mentions & support, Anton! It means the world to me. I'm glad you found it valuable.

Skills mapping ended the chaos in building our squads. I implemented it with my teams and added interests too—key because teams excel not just on skills, but when passions align with business goals.