Engineering velocity on steroids

What a 10x team looks like

When I joined Weave, I gained access to engineering metrics across hundreds of teams. This gave me the chance to try answering something that has always interested me - what do the most productive teams actually look like in the day-to-day?

Today, I brought Sumanyu (founder, CEO, and still-shipping engineer at Hamming AI) to share his secrets. We had a long conversation about how his 6-person team (plus 2 interns) moves faster than most 50-person engineering orgs.

We’ll cover the specific experiments that worked:

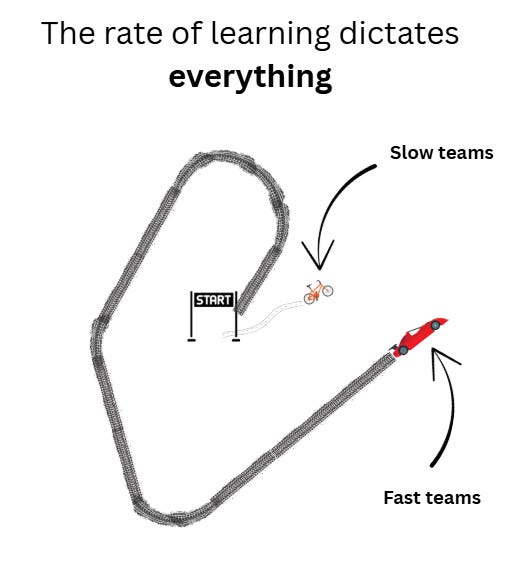

Obsessing about velocity - Why learning rate dictates everything else

MORE meetings for engineers - Direct customer access instead of translation

The new PR process - Architecture reviews before code, AI triage, sub-hour merges

Testing & quality - The next frontier: speed without regressions

The CEO still ships - The “Elon algorithm” for finding real bottlenecks

Hiring interns - Learning rate over accumulated knowledge

🎤 to Sumanyu!

Why I’m obsessed with Engineering velocity

The saying “the rate of learning dictates everything” stuck with me since my Tesla days.

I know there’s a common belief that moving fast means building the wrong thing faster. People say, “It’s better to go slow in the right direction than fast in the wrong one.”

In physics, every vector has a direction and a magnitude. The problem with that advice is that finding the right direction takes experimentation. You need speed to experiment. Understanding the right direction takes time, and having a bigger magnitude (speed) helps you learn faster.

To learn fast, you must do 2 things

Ship fast

Talk to customers a lot

Business outcomes come later. Teams that move twice as fast, learn twice as fast, and are then able to address their aim faster. If it takes you two months to ship something new, your learning cycle is two months. But if you can ship something in a week, you’ll know much faster if it’s a hit or not. Is it actually working or not working?

After YC, we had a huge demand for Hamming (AI voice agents testing) but our product was hard to use and underwhelming. We’d taken shortcuts to hit the intense program milestones. So we did something a bit counterintuitive: we spent the next 8 months (myself, 5 engineers, 2 interns) rebuilding it right while turning away customers.

During those 8 months, I started running experiments to increase our velocity:

Having engineers join customer meetings instead of me

Using AI tools to review PRs

Trying different workflows for Cursor/Claude Code (this was very early days)

My problem was that I had no way to know if these experiments were working.

We all know how inaccurate it is to measure story points and lines of code, and I also felt that the number of PRs doesn’t tell the whole story. As a data scientist (and a software engineer), I felt engineering output should be measurable. In my world, everything has a numbers-oriented lens…

That’s why I reached out to the Weave team. Without measurement, everything was happening on vibes.

Anton here: When talking about measuring developer work, people like to quote Goodhart’s law: “When a measure becomes a target, it ceases to be a good measure”. My answer is always Gilb’s law: “Anything you need to quantify can be measured in some way that is superior to not measuring it at all.”

I use the Weave scores as a KPI for us to improve month over month. Every month we got about 20% more effective - adding up to a 9x improvement in the last year! The team also uses the data to track their own velocity and patterns of productivity (better/worse weeks, meeting heavy / meeting light days).

Let’s go over the changes that drove those results:

Experiment #1: Direct Customer Access

I added more meetings to the engineers’ calendars.

As the CEO, I used to talk a lot with customers. I was sort of translating what needs to be done for our engineers. I thought I was protecting engineering time, but I was creating a bottleneck.

I started to notice there was a lot of back and forth between me and the team, and many miscommunications. So I decided to try removing myself from the loop: I just added engineers to a bunch of different Slack channels. They talk to customers directly, and loop me in only when needed.

Yes, engineers now spend 15 minutes here, 30 minutes there, an hour there in customer conversations. But the rate of learning is so high that it’s not a waste - it’s the fastest path to the right solution.

The real waste was me playing telephone. When I summarized customer problems, engineers didn’t feel the pain customers felt, they felt my interpretation of the pain.

Engineers now often ship solutions the same day they hear the problem. The dopamine hit of talking to a customer, having an idea, and deploying it within hours is what helps drive velocity and a much higher learning rate.

I now believe that it’s critical to maximize the bandwidth between the people who have the problem, and the people who can actually solve it. The more distance there is, the more waste happens.

At Tesla and Citizen, we had different mechanisms for reducing this distance, but I believe the same principle applies: reduce the distance between customer pain and the people building the solution. The specifics change, but the underlying pattern holds.

With engineers talking directly to customers, the next bottleneck became obvious: code review.

Experiment #2: Code Review & PR Process

As we got faster at shipping, code review became a bottleneck. LLM reviews aren’t perfect yet - there are still quirks and issues only humans catch. So we split the process into stages:

1. Architecture review (before any code)

The most critical review happens before writing code. For any significant task, a human validates that the architectural approach makes sense. This catches problems when they’re cheap to fix.

2. AI code reviews

We use multiple AI code reviewers (Greptile, Propel, Cubic, Graphite, etc.). Yes, there’s overlap, but that’s the point - we want maximal coverage.

The engineer then uses an internal LLM tool we built to triage the comments. You’re not going one by one, thinking deeply about each one. The LLM gathers context for each comment, and you override with your judgment when needed. Pretty light process.

Important issues get summarized and sent back to an LLM to fix. Once all AI comments are addressed, it goes to human review.

3. Human review

For any meaningful PR, we have a person look over it. Using the 2 steps above, the time to review has dropped a lot - it’s much easier to quickly find the important things.

The result is PR to merge in 1-2 hours on average.

It took trial and error to figure out what combination of LLMs and processes works best for us. We’re still learning - testing new tools and tweaking the workflow every week.

Our speed revealed the next problem: quality.

Experiment #3: testing & quality: the next frontier

We’ve shipped bugs - annoying ones, that frustrated customers (sometimes even regressing things that were already working). That’s the price we paid for moving so fast.

Right now, our focus is to maintain velocity while reducing the bug rate. We don’t think these are in conflict - you can go fast and high quality, but we’re not there yet.

Our approach is pretty simple: you’ve got to write a lot of tests. We have about 10,000 unit tests and a growing set of end-to-end integration tests. But we’ve under-invested in the testing loop compared to the generation loop, which we optimized.

We just hired a dedicated QA engineer whose entire job is to write evals and improve our testing infrastructure. We want the same rigor we apply to shipping features applied to catching regressions.

We believe it’s solvable, that the tools already exist to build reliable testing systems. We just need to apply the same experimental mindset we used for velocity, to the quality problem. That’s our Q4 focus.

None of these experiments would have been possible if I wasn’t in the code myself:

The return to coding

During my 2.5 years at Tesla, I learned to see everything through an optimization lens - every process could be improved with better data or feedback.

I strongly believed (and still do) that we can build our codebase in a way that is optimized for LLMs, and keep improving it over time. The problem is that to do that, I had to actually be part of the engineering team.

As the CEO, I focused mainly on ‘growthy’ things. You have so many things pulling you in different directions, it becomes easy to stop writing code. I made the decision to go from growth back to engineering, and it’s one of the best decisions I’ve made.

I could not optimize the engineering team if I was not an engineer on the team itself. You cannot theoretically solve problems. You have to be in it to know what is problematic. Why is it so hard to ship? What are the blockers? Why does it take five hours to review PR?

My job became: find the most painful bottleneck and work on it with the team. Keep asking why, why, why, and then simplify one problem at a time. That’s what led us to move much faster than others in our space.

This is the same Elon algorithm of simplification I watched at Tesla.

Anton here: for a further read on Elon’s algorithm, I wrote about it here.

I also really believe that EMs can’t continue improving their teams just from the sidelines. The bottleneck and friction points are starting to get very different than pre-LLM. It’s time to get back into the code with your team(s) :)

Building the Right Team (and hiring interns)

We’ve covered many optimizations, but my number 1 tip is to have the right people on the team.

If you have a bunch of engineers who are skeptical about using AI tools, it’s not going to work. You need people who are very bullish and are open to learning new things.

Here’s where I’m contrarian: I hire interns.

Interns and juniors are being overlooked right now in favor of senior folks with lots of experience. That’s an okay strategy, but I’m a risk taker. I’d rather hire for attitude and learning rate.

Software engineering is changing every year. There are newer patterns we’re discovering that are more optimal than the previous years. So we’re not always looking for classical depth, but for the rate of learning, the attitude, and infinite curiosity. Accumulated knowledge matters less when the field is changing this fast.

The intern approach is also partly giving back. I studied at the University of Waterloo, where you alternate four months of study with four months of work, six times. The last two years of my undergrad, I converted one internship into a full-time job. Those early opportunities jump-started my career.

But it’s also strategic. Interns inject fresh ideas and new perspectives, they come in without assumptions about “how things should be done” - and in 2025, that’s often an advantage.

Final words

If you manage engineers, here’s the framework that works for me:

Find the one bottleneck that’s killing your velocity, and work on it with your team every day. No matter how ambiguous or messy the problem is, identify what’s slowing you down the most and attack it directly.

Start with an audit. Ask your team: where do you actually spend your time? Where are the hours going? That audit becomes your roadmap for what to eliminate.

The goal isn’t to optimize everything - it’s to remove the biggest source of waste, then move to the next one. One problem at a time, week after week. That’s how you compound velocity gains.

Discover Weekly

Oct 2025 Updates: Code, Money, and Travel by Tony Dinh. Love following Tony’s journey!

Most teams engineer products better than they engineer teams by Gilad Naor.

Teams that learn fast, win fast, simple as that.

Giving engineers more direct customer access is interesting. Curious how you prevent chaos where engineers prioritise noisy customer complaints over other priorities